Artificial intelligence has rapidly transitioned from a theoretical concept to a ubiquitous utility. It powers the recommendations on our streaming services, the autopilots in our vehicles, and the chatbots that handle our customer service queries. Yet, as these systems become more integrated into our daily lives, a critical question arises: How do we design the bridge between complex, often opaque algorithms and the humans who use them?

The interface is where the rubber meets the road. It is the translation layer that interprets machine logic for human understanding. Consequently, the design of these interfaces carries a profound ethical weight. It is not merely about aesthetics or usability; it is about transparency, autonomy, and fairness. Ethical design in AI interfaces is the safeguard that prevents helpful tools from becoming manipulative "black boxes."

The Transparency Paradox

One of the central challenges in AI design is the "black box" problem. Deep learning models, particularly large language models (LLMs) and neural networks, operate through layers of computation that can be difficult even for their creators to fully interpret. For the end-user, this often manifests as a system that produces a result—a loan denial, a job rejection, or a route change—without a clear explanation.

Ethical design demands that we value transparency over the illusion of magic. While it is tempting for designers to create "seamless" experiences that hide the machinery, this opacity can erode trust. If a user does not understand why an AI assistant suggested a specific product, they cannot evaluate the suggestion's validity. Is the recommendation based on their actual needs, or is it the result of a commercial partnership hidden in the algorithm?

To combat this, interfaces must prioritize explainability. This doesn't mean showing raw code to a layperson. Rather, it involves designing "why" mechanisms—tooltips, confidence scores, or plain-language summaries—that contextualize the AI's output. For example, instead of simply stating, "Here is your investment strategy," an ethical interface would clarify, "This strategy is suggested based on your stated risk tolerance and current market volatility."

Preserving User Autonomy

As AI systems become more predictive, there is a subtle but dangerous risk of eroding user autonomy. Predictive interfaces are designed to anticipate needs, often acting before a user explicitly commands them to. While convenient, this can cross the line into manipulation if not handled carefully.

Consider the design of "nudges"—subtle UI choices that guide user behavior. In traditional web design, dark patterns might trick a user into subscribing to a newsletter. In AI interfaces, the stakes are higher. An AI-driven news aggregator that curates a feed to maximize engagement rather than inform can trap users in filter bubbles, effectively deciding what reality they see.

Ethical design must ensure that the human remains in the loop. This concept, often called human-in-command, asserts that automation should augment human decision-making, not replace it. Interfaces should provide meaningful controls that allow users to steer the AI. This might look like granular settings for content moderation, clear "opt-out" mechanisms for data collection, or the ability to easily override an automated decision. The goal is to design systems that serve the user’s intent, not just the system’s optimization metrics.

The Interface as a Guardian Against Bias

We know that AI models can inherit biases present in their training data. Facial recognition systems have historically struggled with accuracy across different skin tones, and hiring algorithms have shown prejudice against female candidates. While much of the work to fix this happens at the data and model level, the interface plays a crucial role in mitigation.

An ethically designed interface acknowledges the possibility of error. It avoids presenting AI outputs as objective, infallible truths. When a generative AI creates an image or a summary, the interface should signal the probabilistic nature of that content.

Furthermore, designers must consider who they are designing for. Accessibility is a core component of fairness. If an AI interface relies heavily on voice interaction, does it account for users with speech impediments or non-standard accents? If it relies on visual cues, is it usable for the visually impaired? Exclusionary design, whether intentional or accidental, amplifies the unfairness inherent in biased models.

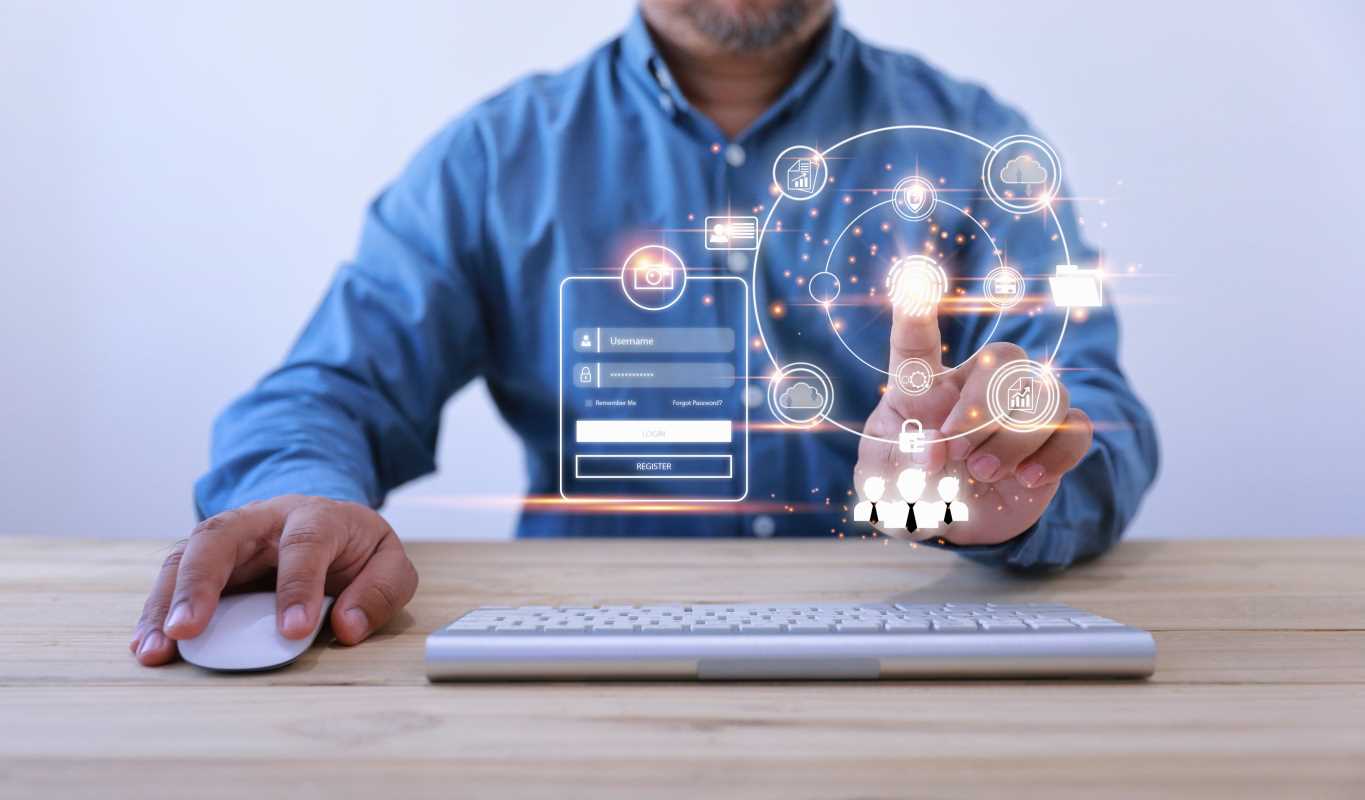

Navigating Data Privacy and Consent

AI thrives on data. To function effectively, these systems often require access to vast amounts of personal information. The standard approach to consent—a dense, unreadable Terms of Service agreement—is no longer sufficient in the age of AI.

Ethical interfaces must move toward informed, dynamic consent. Users should understand exactly what data is being used, how it is being processed, and for how long. For instance, if a smart home device records audio to improve its voice recognition, the interface should clearly indicate when recording is active (perhaps through a hardware light or a prominent on-screen icon) and offer a simple way to review and delete that data.

Designers should also practice data minimization in the UI. Just because an AI can use a piece of data doesn't mean the interface should encourage its collection. Designing flows that ask only for what is strictly necessary respects the user's digital privacy and reduces the risk of misuse.

Actionable Guidelines for Ethical AI Design

How do we move from theory to practice? For designers and developers building the next generation of AI tools, here are actionable principles to guide the process:

1. Clearly Communicate AI Capabilities and Limitations

Do not overpromise. Anthropomorphizing AI—making it sound or look too human—can lead users to overestimate the system's intelligence and emotional capacity. Be honest about what the AI can and cannot do. If a chatbot is a customer service tool, do not design it to feign empathy it does not possess.

2. Design for Contestability

Users should always have the right of reply. If an AI system makes a decision that impacts the user, the interface must provide a clear path to challenge that decision. This "contestability" is vital for accountability. For example, if a content moderation bot flags a user's post, there should be a visible, easy-to-use button to appeal to a human moderator.

3. Indicate AI-Generated Content

In an era of deepfakes and hallucinated text, distinguishing between human-created and machine-generated content is essential for truth. Watermarking visual content or using clear labels (e.g., "Generated by AI") helps users assess the source and credibility of the information they are consuming.

4. Introduce "Positive Friction"

In traditional UX, friction is the enemy. We want everything to be fast and easy. However, in ethical AI design, friction can be a feature. Slowing the user down at critical moments—such as before sharing a sensitive piece of data or confirming a significant automated transaction—forces a moment of reflection. This cognitive pause can prevent errors and ensure that the user is acting intentionally.

(Image via

(Image via

.jpeg)